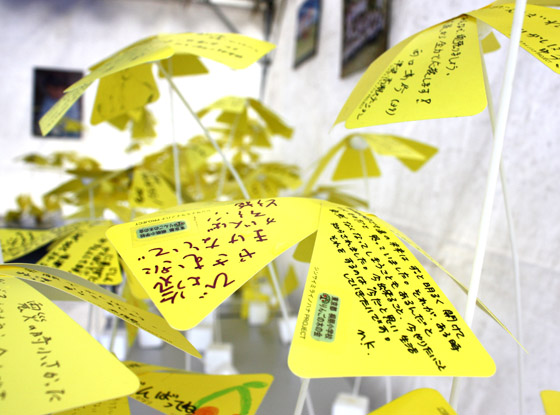

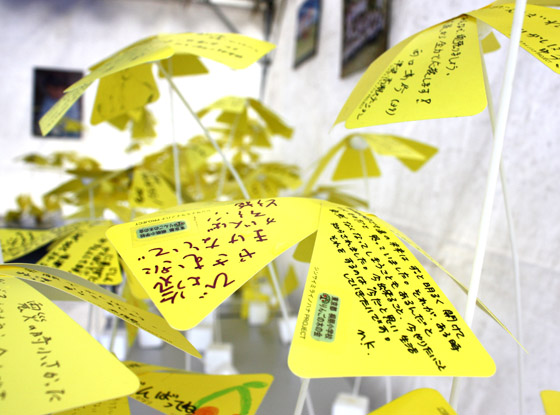

Mr. Nishikawa is engaged in an ongoing project named “Shinsai Mirai no Hana” (lit. “earthquake flowers for the future”), which involves preserving and communicating to future generations the memories and firsthand accounts of the 1995 Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, and nurturing bonds between people. The project took off in Kobe fifteen years after the quake, when it was starting to be felt that increasingly greater proportions of the younger generation knew of the disaster only through secondhand accounts.

“Shinsai Mirai no Hana” keeps growing as more messages pour in

“Shinsai Mirai no Hana” keeps growing as more messages pour in

Each “Shinsai Mirai no Hana” flower is made up of five cards, each inscribed with a personal message pertaining to an earthquake disaster. The project involves displaying these “flowers” in public spaces to inspire more people to spare thoughts on earthquake disasters.

So far, over 100,000 people in Japan and beyond have contributed messages, and their flowers have been displayed in many countries and regions, including Sumatra, Indonesia. Writing freely on the flowers has even provided relief to children who have become withdrawn due to the trauma of losing family members.

By giving people the chance to share their thoughts on earthquake disasters, “Shinsai Mirai no Hana” continues to connect great numbers of people, including but not limited to those directly affected by earthquake disasters.

The “gray” landscape witnessed on January 17, 1995

Mr. Nishikawa was in the second grade of elementary school when the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake struck on the morning of January 17, 1995. From his home in Sakai City, Osaka, he saw the entire view in the direction of Mt. Rokko smothered in gray. It seemed surreal to him that beyond the cloak of gray was the smoldering town of Kobe and its collapsed buildings - and the scene was aired repeatedly on TV. The landscape he saw that morning is about all he recalls of the earthquake. None of his relatives or acquaintances suffered major injury or structural damage, and school resumed the following day. The Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake was brought to mind by recollections of the earthquake published by newspapers and broadcast by TV news programs each year, on January 17. Otherwise, he did not think about the earthquake in particular until about eight years later, when he became an architectural student at Kobe Design University, and, as a result, spent more time in Kobe.

“When you are living in Kobe, the earthquake crops up in casual conversations, for instance between pub-goers who have had one too many. This never happened in Osaka, so it was quite a revelation. In a sense, it was almost as if the earthquake experience constituted part of your identity as a Kobe local.”

Mr. Nishikawa’s interest in the relationship between society and communities gradually grew at university, where he attended a seminar which involved designing a disaster evacuation shelter, and as result of spending time in Kobe, which had become a magnet for people studying earthquake disasters and their effect on communities since the quake.

What design can do for disaster situations

As his architectural studies progressed, Mr. Nishikawa increasingly came to wonder if making buildings was the only role expected of architects.

“It felt to me that architects too often designed buildings almost as if they were works of art, aloof from the culture, history or community of the place where they were sited. As I believed that the role of the architect should be exercised while involving community members extensively in the designing process, I was uncomfortable with the idea of designing a building as a stand-alone.”

At around the same time, the university hosted lectures by community designer Ryo Yamazaki and architect Ryuji Fujimura. Mr. Nishikawa was greatly heartened by the fact that there were architects out there who valued the design process. Winning top prize in a competition of design solutions for earthquake disasters with his entry “Water Triage Tags” also gave him enough confidence that he eventually made up his mind to become a freelance designer. The “Water Triage Tags” adapted the idea of triage tags — used by emergency medical personnel to sort victims according to severity of injury — to managing drinking water under disaster situations.

“Water Triage Tags,” a design entered to a competition of design solutions for earthquake disasters

“Water Triage Tags,” a design entered to a competition of design solutions for earthquake disasters

“I came to think that architecture and design have in common the capacity to guide “scenes populated by people” to better directions. The realization that architectural skills can be exercised without necessarily building a physical structure gave me the courage to choose the career of designing solutions to social issues.”

“Unless we do it, who will?”

Mr. Nishikawa’s first involvement with the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake came shortly after he launched his professional career, in the form of an event associated with a TV documentary Mirai wa Ima (lit. the future is now) produced by NHK. Intended to inspire reflections on the current state of Kobe, the program documented Kobe-born actor Mirai Moriyama, who experienced the earthquake as a child. He visited Kobe fourteen years after the quake, where he, along with Kobe University students, interviewed people who had lost family members or relatives to the disaster. Mr. Nishikawa was commissioned to create an installation displayed at the public screening venue of the documentary. Entitled Shinsai Mirai no Ki (lit. earthquake tree for the future), the object bore messages contributed by members of the public, who were invited to write freely about what the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake meant to them personally. He was chosen because his water triage tags caught the attention of an NHK employee. Involvement in this project, and learning about the bereaved who still suffered emotionally despite Kobe’s outward recovery, brought home to Mr. Nishikawa the fact that no single picture can accurately portray post-earthquake Kobe.

“The screening event was well-attended, especially by young women, helped in part by the popularity of the starring actor Mr. Moriyama. The event proved successful in bringing the attention of otherwise indifferent people to the earthquake disaster, but at the same time, it also made me feel more strongly about the need to share with the younger generation the personal experiences of the earthquake, and I felt that the task had to be carried out by ourselves, and nobody else.”

The urge led to “Shinsai Mirai no Hana.”

Shinsai Mirai no Ki created for a film-screening event when he was a university student, was one of Ryo’s starting points

Learning alongside Kobe’s young people who do not know the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake firsthand

Shinsai Mirai no Ki created for a film-screening event when he was a university student, was one of Ryo’s starting points

Learning alongside Kobe’s young people who do not know the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake firsthand

Twenty years have passed since the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, and many young people who were born and raised in Kobe after the earthquake were among the volunteers working in localities affected by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. Mr. Nishikawa believes that it is his mission to learn about, communicate to the younger generation, and leverage to a greater extent Kobe’s capacity as a community with an active volunteering and NPO scene, resulting from its earthquake experience.

A charity event for Tohoku, attended by many young people who grew up in Kobe after the earthquake

A charity event for Tohoku, attended by many young people who grew up in Kobe after the earthquake

“I have a real sense that each person has his or her own Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, specifically because what I know about the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake is based not on my own experience but on accounts of many people who did go through it. So I think, for the generation born after the quake, a good place to start would be to admit frankly their lack of firsthand knowledge. Otherwise, we risk missing something we might learn from witnesses, and besides, feigned knowledge will sooner or later show through. Unless we are honest, we can never expect witnesses to share what are to them very disturbing experiences.”

The 2011 Tohoku earthquake and Ishinomaki Café

On March 11, 2011, northeast Japan was hit by a massive earthquake and tsunami. Mr. Nishikawa promptly joined others for volunteer work in disaster-struck localities, and at the same time displayed hana (“flowers”) or messages of encouragement at the evacuation centers set up at gymnasiums.

“Initially, I had doubts as to the worth of an activity like hana at a time like that. But as we went on making hana with children sheltering at the center, where they were enduring communal living, the children’s faces started to light up, brightening up the overall atmosphere of the evacuation center just a little. This reassured me that I was doing something worthwhile, something relevant to the time and place.”

Co.to.hana is currently involved in Ishinomaki Café, a post-disaster rehabilitation project run by Ishinomaki City’s high school students in partnership with a number of other NPOs. The project was prompted by fear over the community’s youth population drain, since tsunami damage to local businesses in coastal areas meant loss of employment. To prevent the rebuilt Ishinomaki from becoming devoid of young people, the project encourages efforts to identify local “resources” through interviews of local residents conducted by high school students involved in the project.

Ishinomaki Café, operated in partnership with Ishinomaki City’s high school students and graduates

Ishinomaki Café, operated in partnership with Ishinomaki City’s high school students and graduates

Ishinomaki Café hosts activities such as developing products in partnership with local seafood companies, and interviewing rice growers about their crops. It is a very well-designed café, with a welcoming seating area and an open kitchen. The café’s name, concept, logo, menu and décor were all devised from scratch jointly with local high school students. Mr. Nishikawa’s long-held belief in involving people in the process of designing the buildings and places they will inhabit or use, is beginning to take shape in Ishinomaki, providing a beacon of hope to the local community. He argues that this and other community building efforts are a form of disaster mitigation. For example, the community formed by users of Minna Noen, a community farm Co.to.hana operates at an urban, vacant plot in Osaka City, will most certainly provide a means of joining, thereby offering protection to, community members in the event of a major disaster.

Minna Noen in Kitakagaya, Osaka City, brings local residents closer to each other through farming

Minna Noen in Kitakagaya, Osaka City, brings local residents closer to each other through farming

Belonging to more than one community, no matter how small, can prevent individuals from becoming isolated in emergencies, because where one community suffers, another can assist. When designing a “place,” a building, for instance, starting the design process by considering the type of community the place will host is arguably a very organic way of creating a safety net.

Interviewed and written by Yoshihito Higashi

This article was created with the cooperation of

greenz.jp.

![]() a designer

a designer JP | EN

JP | EN JP | EN

JP | EN

“Shinsai Mirai no Hana” keeps growing as more messages pour in

“Shinsai Mirai no Hana” keeps growing as more messages pour in

Shinsai Mirai no Ki created for a film-screening event when he was a university student, was one of Ryo’s starting points

Shinsai Mirai no Ki created for a film-screening event when he was a university student, was one of Ryo’s starting points A charity event for Tohoku, attended by many young people who grew up in Kobe after the earthquake

A charity event for Tohoku, attended by many young people who grew up in Kobe after the earthquake Ishinomaki Café, operated in partnership with Ishinomaki City’s high school students and graduates

Ishinomaki Café, operated in partnership with Ishinomaki City’s high school students and graduates Minna Noen in Kitakagaya, Osaka City, brings local residents closer to each other through farming

Minna Noen in Kitakagaya, Osaka City, brings local residents closer to each other through farming