Jin Mayama is renowned for his business novels including “Hagetaka.” In March 2013 “Soshite Hoshi no Kagayaku Yoru ga Kuru” (And Then the Starry Night Will Come) was published, a completely different story from any he had written previously. The novel’s theme was the Great East Japan Earthquake, based on his unforgettable experience of another huge earthquake in Kobe 20 years ago.

Part I: Road to a Novelist

―What made you decide to become a novelist?

Part I: Road to a Novelist

―What made you decide to become a novelist?

I have been a contrary person since I was in elementary school. I always looked at things differently from other children. For example, when children played soccer together with friends, they would gather around the ball to try to get it. But in this situation I just waited for the ball to come to me from a place where no one was around. The instant the ball came to me, I shrewdly took the opportunity and made a shot on goal. I was such a kind of boy. I could never help but say out loud what I was thinking. In classroom discussions, I often raised my hand and argued against other children’s opinions. On such occasions, I felt that my classmates were annoyed with me, as if they were saying, “Here he goes again.” I came to worry about my futureas long as my character remained unchanged, it would not be easy for me to live the rest of my life. In those days as I read many novels I began to think vaguely that if I could become a novelist I would be able to communicate to many people what I wanted to say, by taking advantage of my way of viewing things.

When I became a senior high school student, I again thought over my future, in view of my characteristics, school performance, what I was interested in and what not, as well as the circumstances I was in at that time. After contemplation I concluded what I wanted to be was a novelist after all.

―What kind of novelist did you want to be?

I was especially fond of novels focusing on social issues and stories about conspiracies. When I was in high school, my favorite authors were Toyoko Yamazaki and Frederick Forsyth. Back when I was in elementary school, I wanted to be a doctor. After I went to high school, it turned out I was not good at natural sciences. At that time I read a Toyoko Yamazaki novel, “Shiroi Kyoto (The White Tower),” from which I learned it is possible to get many people interested in medicine through a novel. This was really a major breakthrough.

I examined the backgrounds of some of my favorite novelists, and found that many of them had worked as a newspaper reporter or a news service correspondent. I decided to be a newspaper reporter as a step toward becoming a novelist, because I thought their way of gathering and pursuing information on social issues suited me best. I really admire the way Toyoko Yamazaki wrote novels in that she communicated social issues and conveyed the appeals of characters using simple, natural and easy-to-understand words. I thought this writing style was the most suitable for me.

―After you graduated from university you became a newspaper reporter. Why didn’t you decide to continue as a journalist?

Because I thought entertainment was the most effective way to make people who are ignorant of the world gain an interest in social affairs. Newspapers are less effective in this regard, no matter how hard newspaper reporters endeavor to expose social issues. Novels can communicate such issues more easily than news articles. If a novel on social issues is made into a TV drama or a movie, the issues featured in the story will be communicated to a much larger number of people. With this view in mind I never changed my wish to become a novelist. In my days as a newspaper reporter, I always gave my all in my work, no matter how disastrous the incidents were that I had to report, because I believed such an experience would help me create wonderful novels someday in the future.

Part II: What he decided after having experienced the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake

―Where were you when the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake happened?

―Where were you when the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake happened?

I was at home in Kobe. Back then I had just become able to earn my living as a freelance writer while writing novels for mystery writing competitions for new authors. I had been writing a manuscript until 30 minutes before the earthquake occurred. Soon after, as I was lying on the bed in my first floor apartment, a big jolt came. At first I thought it was a meteor or that a truck had hit my apartment building. But the shock came vertically, so I knew it was an earthquake. First, I figured that the epicenter was right under my apartment, and next I felt I would die. When the long-lasting vibration stopped at last, I wondered why I remained safe, and then I felt a rush of relief – “I’ve survived!”

―How was the situation in the areas surrounding your home?

When I cautiously went out of my apartment to look at the situation, almost everything remained unchanged. But when I went to the neighboring station, I saw railway tracks bent and twisted like spaghetti. Later the electricity supply was restored, and it was at the moment when I saw scenes of Sannomiya burning on the TV screen that I realized how lucky I was. The epicenter was underneath Awaji Island, less than 10 km from my home. A large number of earthquake casualties lived in places much further away from the seismic center than where I lived. I felt guilty for having survived. It was very sad and heartbreaking.

―I heard you decided to write a story about an earthquake based on your experience someday in the future.

I had never believed in God or destiny, but I came to think I could survive the disaster because I was allowed to live to write novels. So I decided that someday in the future I would write a story about an earthquake, if I could become a novelist.

―How did the experience influence your work?

―How did the experience influence your work?

After the earthquake I suffered a sharp drop in income, because most of my work was related to promotion of the entertainment industry. To make up the income loss, I started to work as a business book writer with the help of an acquaintance living in Tokyo. During the process of completing a hardcover book I acquired the basic skills to write a novel. In the second year after the disaster, I resumed writing novels for literary prize competitions. In those days, I used to work as a freelance writer until 1:00 a.m., worked on a novel from 1:30 a.m. to 3:30 a.m., woke up at 8:00 the next morning and then went to gather information.

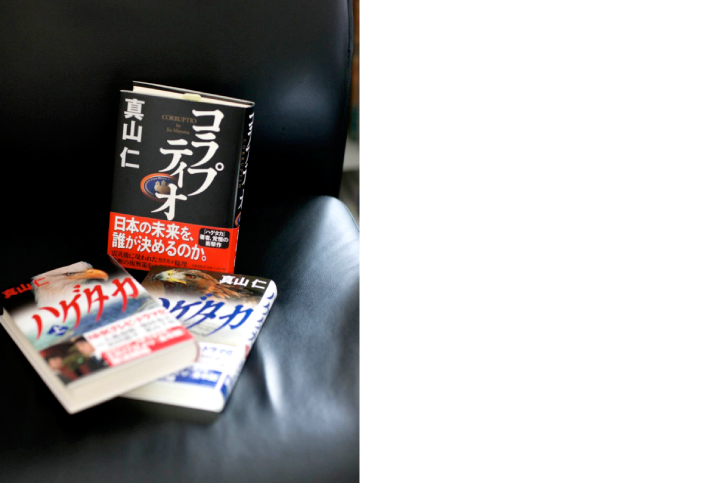

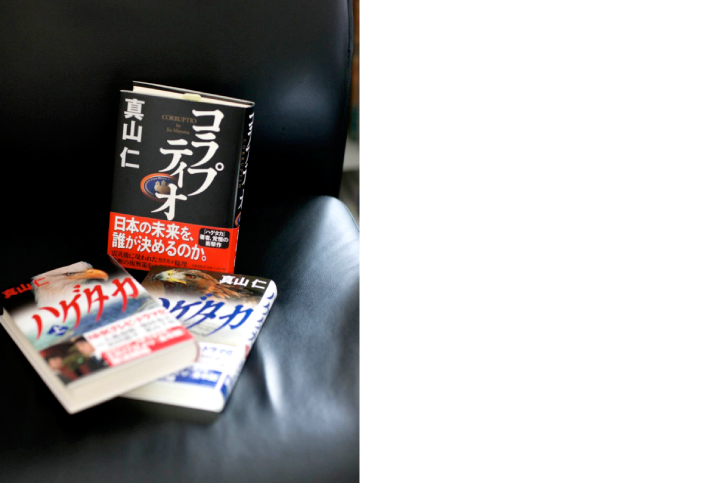

Top: “Corruptio,” a unique near-future political story about Japan after it experienced a huge earthquake. (Now out in paperback by Bunshun Bunko Ltd.); Front: “Hagetaka (Part 1 and Part 2) (Now out in paperback by Kodansha Ltd.),” a business novel featuring investment funds, which was later made into an NHK TV drama, receiving a very positive response from viewers.

―In 2004, you finally made your debut with Hagetaka.

Top: “Corruptio,” a unique near-future political story about Japan after it experienced a huge earthquake. (Now out in paperback by Bunshun Bunko Ltd.); Front: “Hagetaka (Part 1 and Part 2) (Now out in paperback by Kodansha Ltd.),” a business novel featuring investment funds, which was later made into an NHK TV drama, receiving a very positive response from viewers.

―In 2004, you finally made your debut with Hagetaka.

Before making my debut as a novelist, I co-wrote a novel with another writer about a life insurance company in danger of bankruptcy under a different pseudonym. After the book had a certain degree of success, I was allowed to make my solo debut as a novelistmy long-cherished wish. So I wrote Hagetaka.

Soshite Hoshi no Kagayaku Yoru ga Kuru, a story about the Great East Japan Earthquake

―“Soshite Hoshi no Kagayaku Yoru ga Kuru” was a completely different story from any of the other novels you had written previously. The story highlights various issues in earthquake-stricken areas through interactions between Mr. Onodera, an elementary school principal who moved from Kobe to Toma Daiichi Elementary School, a school in an area affected by the earthquake,and the children at his school.

―“Soshite Hoshi no Kagayaku Yoru ga Kuru” was a completely different story from any of the other novels you had written previously. The story highlights various issues in earthquake-stricken areas through interactions between Mr. Onodera, an elementary school principal who moved from Kobe to Toma Daiichi Elementary School, a school in an area affected by the earthquake,and the children at his school.

Readers of the novels I had written thus far may have imagined the story would be about conflicts between the Minister for Reconstruction and a local prefectural Governor when they heard my novel would be set in a quake-hit area. However, in the book, the most important point is what ordinary people can do under such extraordinary circumstances, with the main characters being an elementary school principal and children,.

Although I wanted to write a story about an earthquake since my debut, I couldn’t do so because I couldn’t decide specifically what to write. Several months after the Great East Japan Earthquake in March 2011, I was asked by a publisher to write for its magazine which featured short stories to encourage disaster affected areas. In response to their requests I went to the disaster areas several times to gather information. In the course of this process, I became concerned about the attitude of the media when they communicated information about children in the affected areas. It was always like this: “Children are great. They are cheerful and make people around them happy even in the affected area.”

But this was not true. Children would behave in such a way instinctively when adults become depressed and feel their spirits sinking. Immediately after the disaster in Kobe, children endured their hardships, but the following year it turned out that an enormous number of children were suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and this became a serious problem. To avoid the same situation as in Kobe, I made children spur on adults in the story.

―Mr. Onodera was also a victim of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake.

―Mr. Onodera was also a victim of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake.

In my novel I wanted to dispatch a person who went through hardship at the time of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake to an affected area in Tohoku. By doing so, I could write about stories that the media couldn’t report or inform on in depth. I believed there were some things that could be communicated only by people who had gone through the same experience. In my novel children do not speak the Tohoku dialect, because I wanted to picture them as more rational than the adultsin contrast with the emotional Kansai dialect-speaking school principal. I wanted to create a story setting where rational children would scold adults. Through the novel I wanted to communicate the message “You don’t have to try so hard” to disaster sufferers. The novel is comprised of stories with different themes and conveys to readers issues on volunteers and structural remains left after disasters (*1). I hope this novel encourages readers to think about disaster areas.

―So you wrote the story for people in Tohoku.

The most important point was that I wanted to encourage the people in Tohoku. In other words, if they don’t work hard they will not be able to reconstruct their own towns, let alone restore them. In addition, I wanted to communicate to them that it is important to develop their town into a new one, not to restore it to the original, depopulated one without workplaces for young people.

I received a question from many readers about the story of Toma Daiichi Elementary School in the second year, so I decided to write it. I’m planning to start a new series of the story by the end of this year.

―What should Kobe tell others as the city that experienced the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake 20 years ago?

―What should Kobe tell others as the city that experienced the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake 20 years ago?

It’s essential to think about what should be told. Is it actions to take at the time of a disaster? Or how to overcome hardship when you have lost something precious in the disaster? It differs from person to person. Moreover, it is necessary to tell stories or take actions that make people involved in it and think about it as their own issue, instead of talking about their respective stories only in a unilateral way. It is important to talk about disasters as a universal issue. Through these efforts, while listening to such stories people may think about the issue of the disaster as their own issue.

*1 Structural remains left after disasters: Buildings which were severely damaged by an earthquake and left as they are to serve as a reminder of the disaster and as something from which people in the next generation can learn the lessons of the disaster.

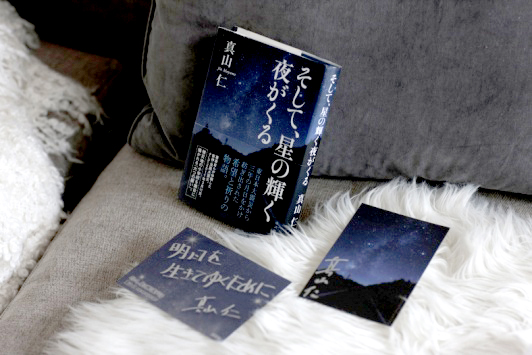

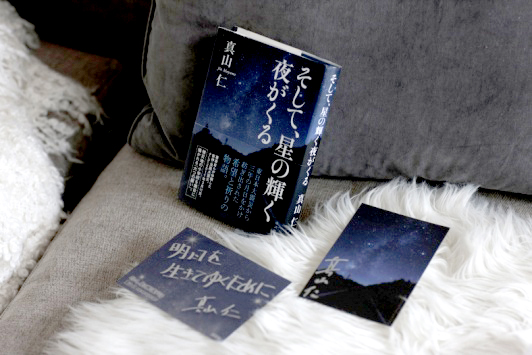

Soshite Hoshi no Kagayaku Yoru ga Kuru written by Jin Mayama, Kodansha Ltd.

Immediately after the Great East Japan Earthquake, Teppei Onodera moved from Kobe to Toma Daiichi Elementary School, a school in a disaster-affected area, as a disaster area support teacher. Onodera himself was a victim of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake. Through interactions with children, he faces various issues in the quake-affected areas. This is a series of six short stories written based on several different themes including the dead and the living, the nuclear power plant accident, volunteers, structural remains of disasters, and memory and oblivion.

(Interviewed and written by Yumiko Takayama)

![]() a novelist

a novelist JP | EN

JP | EN JP | EN

JP | EN