![]() an “Ikumen”

an “Ikumen”

JP | EN

JP | EN

JP | EN

JP | EN

I was living in a family of five – my parents, two younger sisters and me – in a hillside area in Nada Ward, Kobe City. As our apartment house stood on solid ground, both my family and the building itself suffered no damage. So, even after twenty years, I somewhat felt I was not qualified to talk about the earthquake.

We were soon able to get in touch with my paternal grandmother, who was living in the neighborhood. Then we found smoke rising in the area along the JR line near Nada Station, where my maternal grandmother and aunt lived. My father and I rushed there by car. As we went down the hill, the situation became more and more awful … I still can’t forget that scene. My grandmother’s house was leaning, but both my grandmother and aunt were not hurt, having evacuated outside in blankets. Just afterwards, a fire broke out in the neighborhood and my grandmother’s house was completely burnt down.

After the earthquake, seven of my family members, including my grandmother and aunt, lived huddled in the apartment house. We secured water for drinking and washing from the river next to the building, and my relatives brought us relief goods. I don’t remember having led a very inconvenient life. I was a high school student at that time, and maybe I didn’t really know what it was to “rebuild our life.”

Cell phones were not common in those days. With a student list in my hand, I traveled along the National Highway Route 2, on a borrowed bicycle, in order to confirm the safety of my friends and junior fellows. When school was resumed after two months or so, I learned that one senior and one junior in my club, two or three other students in the school, and one teacher, had lost their lives. All of the students in my grade were alive.

We couldn’t use the gym, so we practiced in the science and physics laboratories. All of us, including juniors who lost their peers, worked hard. Some people said we should not be doing such a thing, but club members voluntarily gathered, simply wishing to play together. Maybe we also thought that we could make someone happy.

So my memory about the earthquake is connected to my high school days. After graduating from high school, I commuted to a university in Osaka from my parents’ house. Then I moved to Yao City in Osaka Prefecture, when I began working. My life was deeply associated with Osaka for about ten years, so I don’t know much about Kobe after I came of age. I have always felt a kind of diffidence for not having experienced the death of a close person.

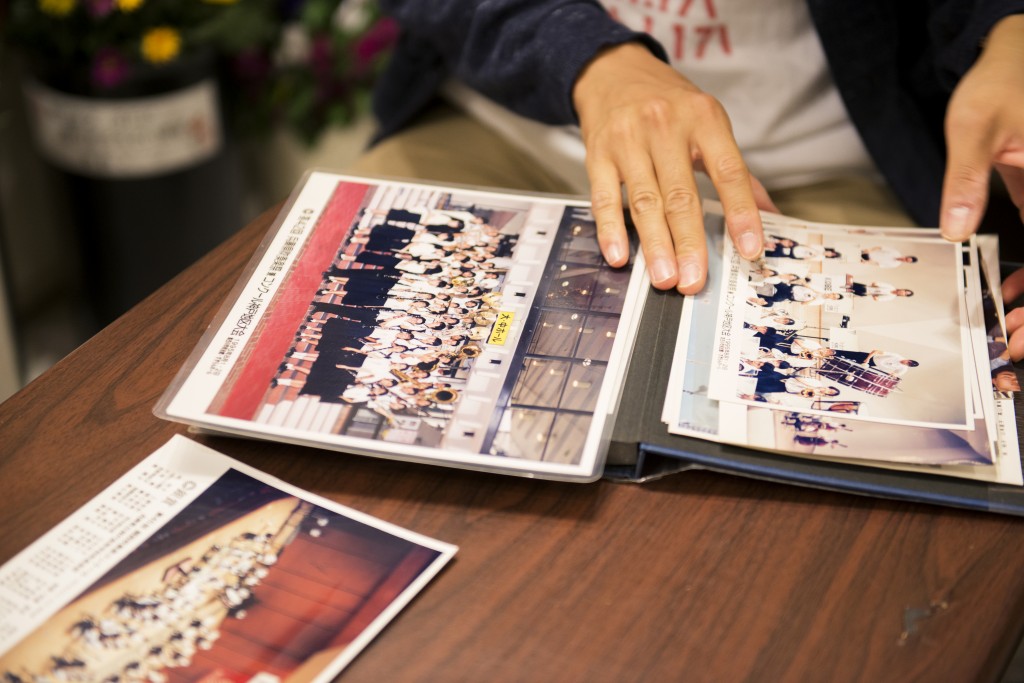

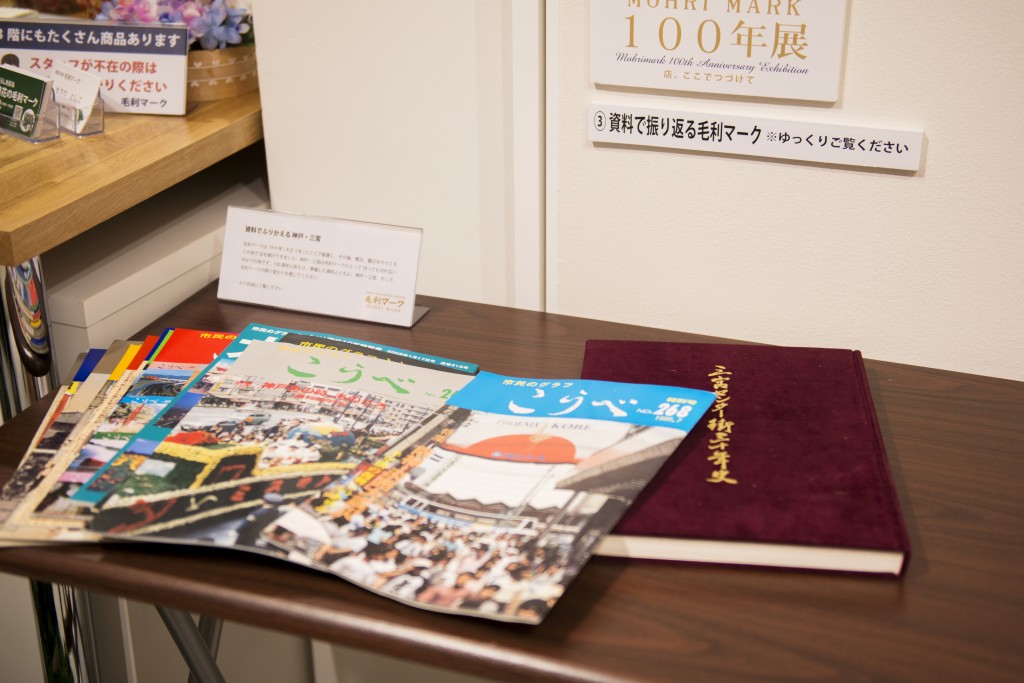

I was born and brought up in Kobe, and I had vaguely thought that I would return to Kobe someday. My wife was one of the three sisters, and Mouri Mark had no successors. So my wife’s father totally welcomed me. At that time, I wasn’t aware that Mouri Mark had a 100-year history. I just thought that the shop in Sannomiya had been, and would be there for a long time. But at least I can say that I have decided to run the shop with my own will.

Mouri Mark sells trophies. The project began simply with my ideas: “If there are more opportunities to praise someone, then maybe the opportunities to use trophies will increase as well” and “Praising someone is a good thing. I hope that the culture of praise will prevail.”

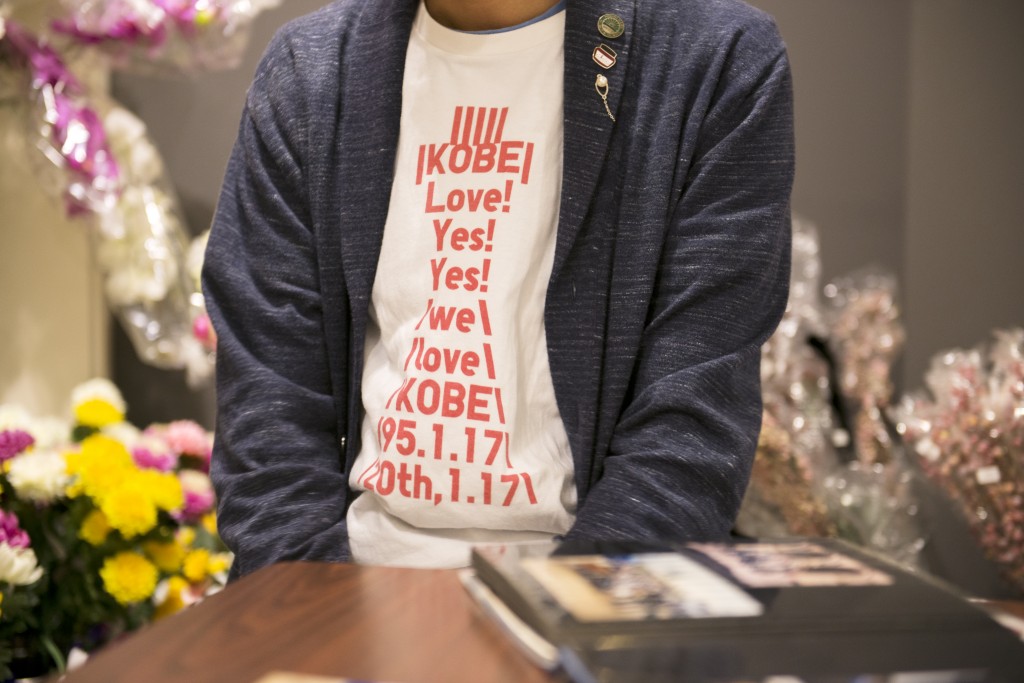

When I was looking for ideas for a self-produced awarding ceremony, I had my third daughter and began to work for shorter hours for a month. I left the office one hour earlier and went to the nursery school to pick up my elder daughters. The routine of finishing my work one hour earlier, coming back home, riding my bicycle and picking up my daughters was much tougher than I had thought. Then one day, I read a newspaper article saying that over 80% of men take paternal leave in northern European nations (about 1% in Japan). I was inspired by the sentence at the end of the article: “Why not hold an Ikumen Award or something?” I thought, “Yes! This is it!”

Though the project name had “Kobe,” I didn’t mean to collect Ikumen’s episodes only from Kobe; I intended to collect such episodes from all over Japan, and output their lifestyle from Kobe.

2010 was the year when the revised Act on Childcare Leave and Caregiver Leave came into effect. At the end of the year, the word “Ikumen” was included in the top 10 list of the Buzzwords-of-the-year contest. The Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare started the Ikumen Project, and similar events were held nationwide. Kobe was the pioneer in the Ikumen movement.

Five years have passed since I began this project. The word Ikumen has become popular, but was focused on as a trend that has nothing to do with families having no children. To have the project serve not only as an awarding opportunity for fathers, but also as an opportunity to interact with children, I changed the name of the event to “Kobe Ikumen Day” in 2013. I believe that Kobe will be an even better place if everyone naturally watches over children, whether they are their own children or not.

Through various activities, I hope to create an environment where everyone – including those living or working in Kobe – thinks that the city is a good place. I feel again that the 20th anniversary of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake should be considered a good opportunity for this.

As a citizen to create the future of Kobe, I will keep on thinking what I can do, and how everyone can be committed to this dream. I hope that I can contribute to Kobe, even a little, so that I can say “I love Kobe!” from the bottom of my heart.

Atsushi Fujii

Director of Mouri Mark Ltd. and Chairperson of the Kobe Ikumen Steering Committee. He intends to increase the opportunities for trophy presentation and spread the culture of praise, showing appreciation to those who perform good deeds. When his third daughter was born, he experienced shorter working hours for the purpose of parenting, for a month, and learned just how hard parenting is. To answer his own desire “Please appreciate my parenting efforts!” and to spread the culture of praise, he launched the Kobe Ikumen Award in 2010.