![]() a butcher

a butcher

JP | EN

JP | EN

JP | EN

JP | EN

Every company needed to recruit university graduates, and all of my seniors were employed by famous trading houses. Fortunately, I also received many job offers. After wavering, however, I decided to succeed to my parents’ shop with my younger brother. My parents never told us to do so, but I made this decision because I grew up while watching them working.

My father is a stubborn old man, born in the early 20th century. He never made an exception of me, being his first son and successor. He told me: “It is true that having graduated from university is a great asset to you, but just keep it to yourself.” Our family had two shops and ten workers at that time, but no one taught me what to do. Newcomers had to learn by seeing how my father or other seniors did their jobs.

And then the earthquake occurred. Luckily, it was a Tuesday; I mean, the regular holiday of the market, so we didn’t suffer any fires. What if it had not been a holiday? Just the thought of it makes me shudder. After 5:30 am, tofu shops begin preparing to deep-fry tofu.

Photo:Nishimura talking about the aftermath of the earthquake. “I called on younger men for cooperation and started a night watch on the day of the earthquake.”

Photo:Nishimura talking about the aftermath of the earthquake. “I called on younger men for cooperation and started a night watch on the day of the earthquake.”I looked around to find all the shops’ frames squashed and the shutters flapping in the wind. It was such an unsafe situation. Every shop had safes and stocks because they had been doing business as usual until the day before. We couldn’t do anything sitting in the evacuation center, so we decided to start a night watch from the day of the earthquake in some groups. As I was the chairperson of the cooperative and the community association leader, I called on people around me for help and was able to gather some 30 people.

I also asked them, “If you have some warm foods or alcohol, please bring them to me, but only bring what you can spare,” and cooked the ingredients for evacuees in large drums. I did whatever came to mind. I was able to conduct such activities because I had a good relationship with the market members and neighbors. After the Great East Japan Earthquake, many people referred to the importance of people’s ties. Without help from others, we can’t do anything. What’s more, if there are 100 supporters, we get the power of 1,000 people. I realized the true meaning of “Mastery for Service,” the motto of my old school, Kwansei Gakuin University. That awareness is still alive in me.

Photo:Marugo Market today. Even after the disaster, they have kept the nostalgic streetscape that evokes the image of the golden days of Japan's postwar economic growth.

Photo:Marugo Market today. Even after the disaster, they have kept the nostalgic streetscape that evokes the image of the golden days of Japan's postwar economic growth.In such a terrible situation, all shopping streets and markets in Shin-Nagata cooperated to host the “Reconstruction Bazaar” in 1999, assisted by a 20 million yen subsidy from the Hyogo Prefectural Government. We managed to make a success of the event. Before that, events were held individually by each shopping street or market. It was the first challenge for us to work together as one, over the boundaries of associations and communities, which ended in success. Inspired by the spontaneous voices of the participating shops, “Don’t make this a one off”, we have continued monthly community-building meetings for the 15-odd years since then.

Photo: The huge Tetsujin 28-go Monument with a height of 18 meters and weight of 50 tons, completed in October 2009. It attracts fans from around the globe. (©Hikari Pro/ KOBE TETSUJIN PROJECT 2009)

Photo: The huge Tetsujin 28-go Monument with a height of 18 meters and weight of 50 tons, completed in October 2009. It attracts fans from around the globe. (©Hikari Pro/ KOBE TETSUJIN PROJECT 2009)I had the idea of revitalizing this area that has lost its function as a market by adding the concept of “Asia-yokocho” (Asian alley). We rented vacant shops from former shop owners, subsidized interior finishing costs and rent, and invited two shops selected from many candidates—a Taiwanese food stall and a Thai restaurant. We hoped that, after we closed our shops in the evening, they would attract many visitors to energize the street. However, giving only financial aid was not enough. We couldn’t manage and assist them in the evening, and they failed to get regular customers. They were soon stuck in a dead-end situation.

This time, we planned an event which we, shop owners in the market, could also participate in. During summer, food stalls appear in the Marugo Market once a month. The food stalls include those offered by the shops in the market, as well as an Asian cuisine restaurant that opens on this occasion only. When I decided to host this event, I persuaded the market members into doing the event together. Here again, the awareness of “doing together as one” was important.

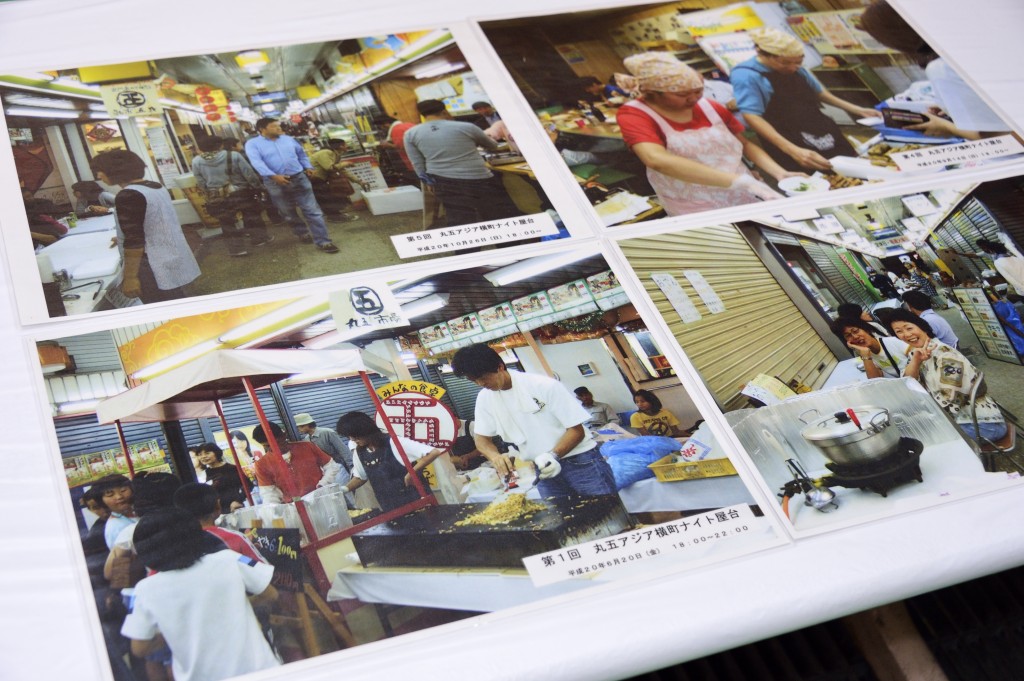

Photo:Marugo Asia-yokocho Night Yatai. Scheduled to be held next year as well, on the 3rd Friday of every month from June to October.

Photo:Marugo Asia-yokocho Night Yatai. Scheduled to be held next year as well, on the 3rd Friday of every month from June to October. Photo:He frequently attends meetings, implements various projects throughout the year, issues a PR paper and participates in events as a member of the Kobe Nagata TMO.

Photo:He frequently attends meetings, implements various projects throughout the year, issues a PR paper and participates in events as a member of the Kobe Nagata TMO.I can’t back out now since I myself have evoked such local revitalization that has surprised everyone—our customers, the Mayor of Kobe, and the shopping street organizers who came to see our projects from all over Japan—and made them say, “What in the world is this?” Of course, we are holding Marugo Asia-yokocho Night Yatai next year. I will continue my job also for my own health. There’s more to come!

Masayuki Nishimura

Masayuki Nishimura was born and raised in Nagata Ward, Kobe. After graduating from the School of Business Administration, Kwansei Gakuin University in 1966, he inherited his family business, “Nishimura Poultry Shop,” as the second generation owner. After the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, he launched projects such as “Marugo-don” (Marugo rice bowl) and “Asia-yokocho Night Yatai” (Asian alley night food stalls) as Chairperson of the Marugo Market Cooperative in search of new opportunities for the market.