![]() a community development promoter

a community development promoter

JP | EN

JP | EN

JP | EN

JP | EN

I learned about the earthquake from the TV news. However, I didn’t feel like doing anything such as reporting on the disaster-stricken areas or anything like that, but just watched the disaster on TV. The news reported that diverse people of all ages were providing support in various areas.

Back then I thought that only special people carried out welfare activities or worked as volunteers during disasters. Actually, I knew almost nothing about Kobe at that time. While watching the news reports on TV, I planned to go to Nagata Ward, one of the areas that suffered the most catastrophic damage.

On TV news, I saw a reporter interviewing a Vietnamese parent and child who were earthquake survivors. They remained silent in response to the reporter’s questions. Many Vietnamese people lived in Nagata. They had come to Japan as refugees and later settled in the area, but in those days most of them were isolated from the local community because they did not understand Japanese. The moment I saw the report, an idea suddenly came to mindI want to go to Kobe to help them. I made up my mind to do so.

The basis for my decision was that it was close to my way of life and the reasons why I had become a newspaper reporter and freelance writer. As the first step of my freelance writer career, I intended to report about Yugoslavia, where people were torn apart by conflict at that time. I felt a strong sense of discomfort about the fact that people in a nation, in which once diverse ethnic groups had lived together in harmony, started killing each other because of ethnic and religious differences, beginning with the collapse of the national government. I really wanted to shed light on such a matter.

The main cause of such problems was a conflict of views and perception gaps between each ethnic groupJapanese, Korean, and Vietnamese residents. What worsened the gap between them was the language barrier: many Vietnamese earthquake victims did not understand Japanese. In addition, there was another problem. The shelter was often reported on by media because it accepted many Vietnamese people, and therefore many relief goods were sent exclusively to Vietnamese people.

We volunteers asked the groups of Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese residents to choose representatives and took a long time to discuss the method of operation of the shelter together in a small group, while we encouraged the ward office to include the shelter in their officially designated distribution route for relief goods.

Photo: Mr. Hibino tackling a support activity in the aftermath of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake (left)

Photo: Mr. Hibino tackling a support activity in the aftermath of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake (left) From such information exchanges, we learned that the greatest problem for Vietnamese disaster survivors was the language barrier. Miscommunication due to the language barrier made us feel as if we had been enveloped in fog. To solve this problem, I asked students from Osaka University of Foreign Studies and overseas students from Vietnam to serve as interpreters for them. From then, problems caused by the language barrier reduced little by little, as if the fog that enveloped us gradually lifted.

It was at that time when we received a suggestion from a South Korean resident of Nagata: “How about broadcasting via radio the necessary information for affected Vietnamese people in Vietnamese?” According to the person, FM Yoboseyo, a multi-language radio station for affected South Korean people started radio broadcasting in Japanese and Korean. FM Yoboseyo was set up at Kobe Korean School inside the West Kobe Branch of Mindan (the Korean Residents Union in Japan) located near JR Shin-Nagata Station, on January 30, two weeks after the day the earthquake hit the area. The radio broadcasts healed the minds of the first-generation Korean residents suffering psychological damage from the disaster.

Information was broadcast on radio not only in Vietnamese but also in Tagalog, English, Spanish, and Japanese. This activity became a springboard to create connections with people of different nationalities. Taking this opportunity, I moved our earthquake survivor support activity base to Takatori Catholic Church, a relief base.

Photo: A statue of Christ commonly known as “Christ Miracle Statue” was spared from damage by the earthquake

Photo: A statue of Christ commonly known as “Christ Miracle Statue” was spared from damage by the earthquakeI thought the disaster revealed problems that had been concealed in society and were invisible to us. Although Kobe had been called an international city, I recognized that the city had many challenges through my experience during the post-earthquake period. Through the support activities I provided, I realized that local residents were striving to overcome their hardships gritting their teeth in spite of their huge damage brought about by the disaster. Seeing people keep fighting on like that, I thought that Kobe would certainly be able to overcome the city’s difficulties someday in the future.

I wanted to continue the radio station for 10 or 20 years as a soapbox for a variety of residents living in Nagata, not just as a way to support disaster victims. To this end, the year after the disaster I obtained approval from the national government to make the radio station an official community radio station. I hope the radio broadcasting serves as a trigger to make Nagata a multi-culture-based community.

Photo: Mr. Hibino (third from right) and his wife (second from the left) at the time of the earthquake

Photo: Mr. Hibino (third from right) and his wife (second from the left) at the time of the earthquakeI owe what I am now to a variety of people I encountered. In particular, I came to know an aspect of Japanese society that I had not known before I lived and worked with people who were often marginalized by their communities. For 20 years since the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, I have participated in community development with local residents. Through these efforts, I could see society from a different perspective, and I became richer internally and have grown personally.

Sometimes I have seen a problematic situation where Vietnamese people I worked with were excluded from Japanese society. To avoid this happening, we took actions such as holding meetings to resolve social problems related to discrimination by adults, and asking newspaper reporters to write articles related to this problem. Japanese local residents, not only those excluded from society, must voice complaints to resolve these problems. Otherwise, Japanese society will not change. I believe such efforts will become a strong power of multi-cultural society.

My foreign co-workers and I set up a food stall offering international cuisine in a festival held every year at a park near Takatori Community Center. At first customers approached the food stall timidly and tasted our foods tentatively. Now, our food stall has become very popular.

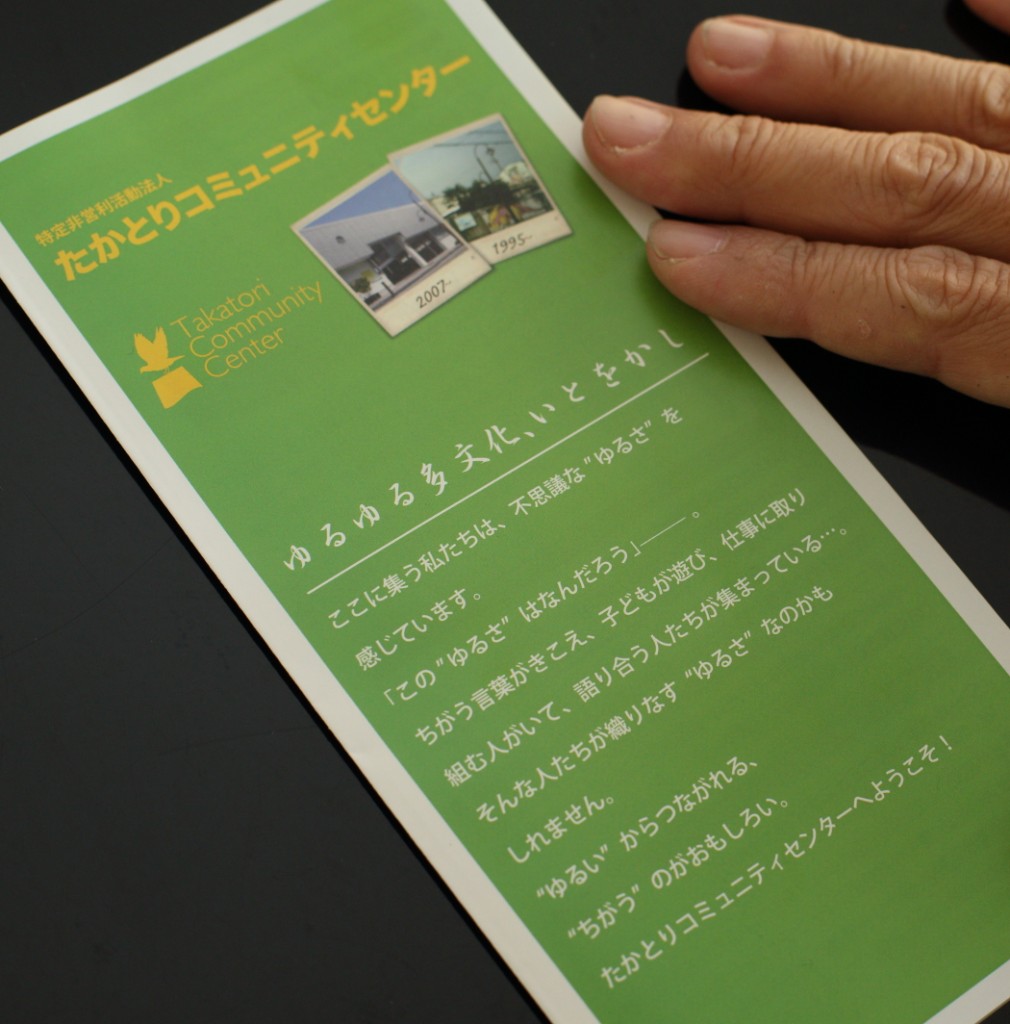

Takatori Community Center’s leaflets include the message “Yuruyuru Tabunka Ito O Kashi (It is interesting to live together with people of multiple cultures in a free and easy atmosphere).” We are tackling the development of a community comprised of various elementsspeaking in different languages, children playing, and people talking and working, in a “free and easy” atmosphere.

Photo: The leaflet highlights the words meaning “Yurusa”

Photo: The leaflet highlights the words meaning “Yurusa”One day, two well-built male university students came to me after my lecture. They introduced themselves as on-line rightists. They said to me, “We feel ashamed to have circulated hate speech about Koreans and Chinese living in Japan on the Internet without knowing they have such histories.” I recommended that they come to Takatori Community Center to participate in activities with various people. Interacting with people of different cultures and nationalities will broaden our horizons.

Although some radio stations started delivering disaster related-information in multiple languages, some still had no idea about multiple language broadcasting. After we told those radio stations about the necessity of multi-language broadcasting, they accepted our opinion and immediately incorporated it in their radio programs. Unlike immediately after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, many radio stations in Tohoku started broadcasting in multiple languages shortly after the disaster. I felt glad that we had continued to carry out our own activities.

Photo: FMYY conveying the voices of local residents to the community

Photo: FMYY conveying the voices of local residents to the community Photo: Mr. Hibino talking about the history of his activities in detail

Photo: Mr. Hibino talking about the history of his activities in detailI believe what people in Nagata and other areas in Kobe learned from the experience of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake was that multiculturalism will become a great asset of society. The other important thing was that citizens should not leave important decisions regarding their own community-related matters to government, but should use their own decision-making abilities to develop their community by themselves.

The word “citizen” includes diverse people in different positions and of different nationalities and cultures. Of course, city officials are also citizens and community residents. Each citizen working in their own position leads to a widening of connections, linking people of different cultures. I am confident that such connections make it possible to realize a multicultural society where it is possible to coexist peacefully.

Junichi Hibino

Junichi Hibino is the Representative of FMYY. He was born in Tokyo and previously worked as a newspaper reporter. He aims to realize multi-cultural and multi-national coexistence and the revitalization of local communities by their residents. He also delivers lectures on multi-cultural education at universities as a part-time lecturer.