![]() an architect

an architect

JP | EN

JP | EN

JP | EN

JP | EN

First, I made contact with my friends in Kyoto to check that they were okay, as I had spent my college days there. But I was not able to go to the affected areas. The situation was far beyond our imagination, and I hesitated to go there because I thought that I might be a nuisance if I went there for help.

When I think back, what I felt after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake and my experiences of village research in Africa, Morocco, and other places around the world have led up to my current activity.

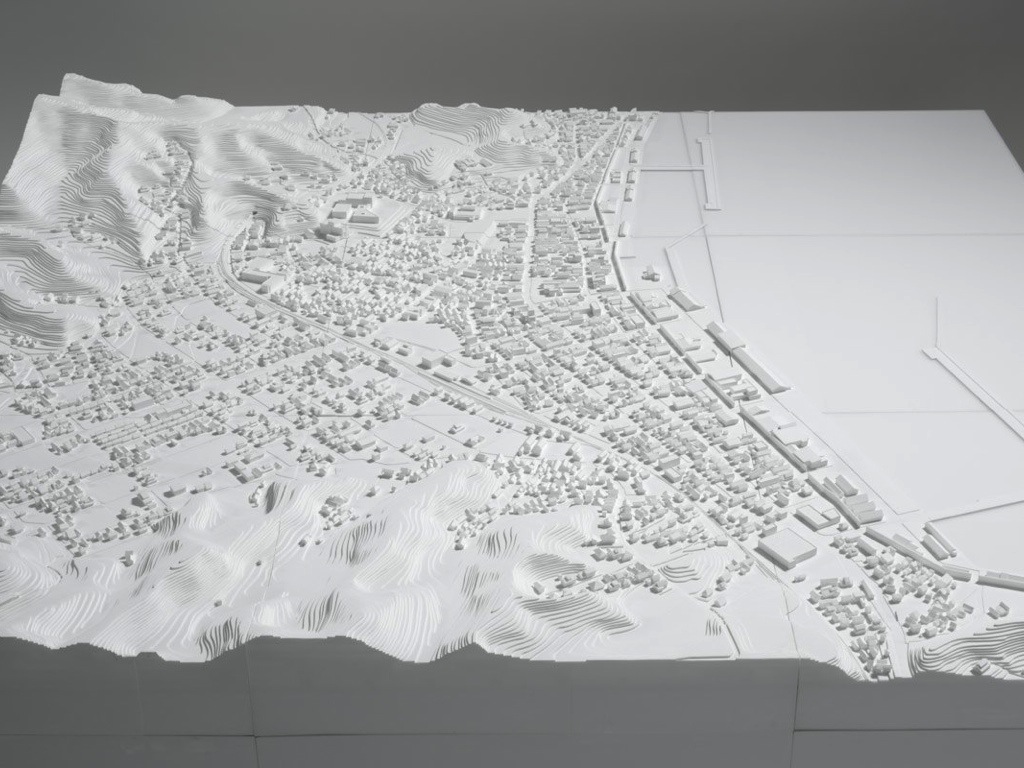

Photo: White scale models waiting to record the memories of the town (Yamada Town in Shimohei district, Iwate. Produced by Nagoya City University and Aichi Shukutoku University, and photographed by Takumi Ota)

Photo: White scale models waiting to record the memories of the town (Yamada Town in Shimohei district, Iwate. Produced by Nagoya City University and Aichi Shukutoku University, and photographed by Takumi Ota) Photo: A workshop in Taro area, Miyako City in Iwate. Colors are added one after another to record the town’s memories (Produced by Ritsumeikan University and photographed by Jason Halayko)

Photo: A workshop in Taro area, Miyako City in Iwate. Colors are added one after another to record the town’s memories (Produced by Ritsumeikan University and photographed by Jason Halayko)Around the world, we can see villages that value their unique culture, and their own distinctive houses. Each of them was created based on the reasons unique to each place.

At the time of the Great East Japan Earthquake, countless towns and streets were lost in a moment. I remembered the towns and villages in the world I had seen during my research, when an idea came to mind that the lost towns must also have had their own particular scenery and lives. That’s why I launched this project.

While worrying about the possibility that this project might give pain to some people, I showed the conceptual drawing to the officials in charge. Then the officials, who had been calmly listening to me, were brimming with tears of joy, saying “We are glad we can see the lost towns again, even in the form of a model.” It was an unexpected turn that made me realize the strong power that each “place” has.

Photo: Two officials of Kesennuma City shed tears of joy upon seeing the conceptual drawing of the scale models. (A scene from the video of the meeting. Video taken by Osamu Tsukihashi)

Photo: Two officials of Kesennuma City shed tears of joy upon seeing the conceptual drawing of the scale models. (A scene from the video of the meeting. Video taken by Osamu Tsukihashi)We displayed the scale models in an open space at the exhibition venue. This allows anyone to participate in the workshop at any time. I chose this way so that people could participate rather casually, without being forced. There must be many people who feel pain when they see the restored town models, and turn and face reality.

For those who say “I lost all of my family members,” we can do nothing but to be there to listen. Curiously enough, as we record their memories, the models change into something that makes us feel the lives of people who actually lived there. I guess that each person’s attachment to his or her place, rather than the restoration of the buildings itself, breathes life into the models.

Photo: Collaborative work by students for the exhibition “311: Lost Homes” in TOTO Gallery-Ma in November 2011 (Photographed by Yoshinori Kuwahara)

Photo: Collaborative work by students for the exhibition “311: Lost Homes” in TOTO Gallery-Ma in November 2011 (Photographed by Yoshinori Kuwahara)An elderly woman, who had run a grocery store in Iwate for 50 years, lost her memory of the past decade as a result of a great shock of the tsunami. One day, she came to the exhibition and was standing face-to-face with the scale models for about 10 minutes. Then suddenly, her face brightened with a smile. The scale models turned on her “switch of memory.” To evoke people’s memory is, I believe, one of the important missions of this project.

It is of course important to raise awareness of disaster risk reduction and a resilient society. At the same time, while the towns undergo decline instead of growth, due to an aging population, we have reached a stage where as many people as possible must take an objective look at their towns and develop awareness of their challenges and solutions. Many of the people who are involved in activities for their community are in their sixties or seventies, and young people tend not to take interest in such activities. I also hope that this project will help local resources, including history, to be shared among all generations.

There are survivors who moved from coastal areas to inland areas after the disaster, and suffer from a feeling of guilt for having fled their homes. I learned that some such survivors have renewed themselves by facing the scale models – this is not a play therapy, though. I recognized the importance of rebuilding the relationship between a person and a place.

It is also a problem that there are people who cannot go back to their hometown and have no choice but to live somewhere else. I hope that they remember the attractive points and history of the place they had lived in, and that I can record their sentiments.

Photo: Exhibition “Iwate: memories of the hometown” held in Morioka Aiina in Morioka City, Iwate in March 2014 (Photographed by Kazuomi Ito)

Photo: Exhibition “Iwate: memories of the hometown” held in Morioka Aiina in Morioka City, Iwate in March 2014 (Photographed by Kazuomi Ito)There are people who have lived on higher ground from the beginning, and those who are going to move to such places. Both of them have opinions which they hesitate to convey to the other party directly, so we serve as a bridge connecting them. Great changes are being made to their own towns through reconstruction projects, and this is a big issue also for those who escaped damage. Many things have been cherished and preserved for a long time, such as the land inherited by a certain family for generations, and the places people had avoided .

You don’t know what a town or village is like until you actually live there. Scale models provide people with an opportunity to recall their memories. “Yes, the town I had lived in was like that.”

Every architectural structure has a “personality.” Originally, architecture was a form of combined art made by attaching master’s techniques to the stream of landforms, landscapes and other beautiful things. We have a sense of discomfort to contemporary townscapes because we see no such combination there. In this individualistic society, it may be difficult to do everything together, but we should at least take an interest in the town and people.

I have always wanted every person living in a house to be an “architect.” By this, the relationship between a house and its residents will improve. In this context, I thought that scale models were necessary for people to accept the fact that they were affected by the disaster. I sincerely hope that this project can help reduce a sense of loss felt by those who have lost the memories of having lived in certain places, or tangible memories such as photographs.

I would like to express my sincere respect to those who have struggled to resolve the issue of solitary death and other problems caused by the collapse of local communities after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake.

Compared to other regions in Japan, I feel that people in Kobe have a stronger affection to their hometown, and this is what makes Kobe special. I think that the key to further improvement of Kobe is to enjoy its old Western streetscapes and unique landforms.

Photo: At the Design and Creative Center Kobe (KIITO), where Tsukihashi’s office is located

Photo: At the Design and Creative Center Kobe (KIITO), where Tsukihashi’s office is locatedOsamu Tsukihashi

Osamu Tsukihashi is the representative of Architects Teehouse and an associate professor at the Faculty of Engineering, Kobe University. He has designed many shops and houses. Since the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, he has been providing support to severely damaged areas, looking to see what he can do in the field of architecture. The Scale Model Project for Restoring “Lost Homes” brings back the memories of lost towns and villages and, in some cases, it also evokes people’s memories. The project, supported by many volunteer students from across the nation, encourages the emotional recovery of affected people.